In much of the twentieth century, the black community heavily utilized the “science” and “methodology” of what is known as “the paper bag test” to determine one’s overall value in society. The test was simple: if a woman’s skin is lighter than a paper bag, she is beautiful, intelligent, feminine, kind, ideal, and if a woman’s skin is darker than a paper bag, she is unattractive, unintelligent, mean, and useless. This is where my story begins.

In looking back on my childhood and early adult years, I realize the impact race had on my life was less grounded on racism, and more on colorism. Colorism is prejudice or discrimination based on the relative lightness or darkness of the skin, generally a phenomenon occurring within ones own ethnic group. I am black and white, but untraditionally so. The ‘black’ side of me comes from Barbados and England with Cherokee Native American, and the ‘white’ side of me is nearly entirely Slavic, coming from Russia, Ukraine, Poland, and Czechoslovakia. In middle school, I personally constituted twenty five percent of my grade’s ‘colored’ population, and I am only half black. I was confronted by race in a way I had never before experienced. I stood out because of how I looked and it made the next three years some of the most miserable of my life. For those years, I was alienated because I was “the black girl”, but in eighth grade, something changed; I became “the mixed girl”.

As if my being black and a non practicing Catholic wasn’t enough, the students and faculty at my school didn’t even accept the ‘White’ side of me. I was half Eastern European, which is a very heavily Jewish region of Europe, even though neither my ancestors, nor I were so. In eighth grade, when prompted to present about our primary region of origin in the world, I chose Poland (since that is the largest percentile representation I have in any country). At the end of my presentation, my teacher, Mrs. Reischer, asked me inquisitively, “But you are mulatto, right?”

For everyone who thinks my teacher just accused me of being a Starbucks drink, let me clarify: “Mulatto” is the slave term for a biracial person, likely born to a slave and a slavemaster, and it equates to “nigger”. I was not offended at all, just confused. I corrected her and went on with my day, still sufficiently confused. What year was it? Was ‘mulatto’ still a noun comfo rtably situated in the vocabularies of our seniors – the wiser of society? Evidently so. I went home and told my black mother what had happened and she smirked. She was equally confused, but utterly amused at the ignorance of society. We never spoke about it in depth.

rtably situated in the vocabularies of our seniors – the wiser of society? Evidently so. I went home and told my black mother what had happened and she smirked. She was equally confused, but utterly amused at the ignorance of society. We never spoke about it in depth.

Race was not an element of my home. My parents were black and white, and divorced. My mother remarried a black man with a quarter French in his background. My step-brother was adopted from Guyana, and is much darker than the rest of us. My little sister took after my step-dad with narrower features and a lighter complexion, making her mistakably Korean. We all looked nothing alike, but still we were everything alike. We understood that we didn’t look the same, but why did it matter?

My parents did their absolute best raising me, to help me define myself as a person, regardless of race. However, due to this, when I entered a world where people are uncomfortable because of one’s inability to fit into one racial bubble on a standardized test, I drowned. Too abstract? Humor me. After the comment in school, I was faced with the paradox that I was different from other people; no one I knew looked like me, and likely, no one ever would. And because of this, I had to establish my place in society and take it for what it was: a shit-show. For much of my life, White people I knew found me threatening. I am almost White, but with undeniable Black qualities. It was kind of like how television aliens are so close to being humans, but once you make them purple and naked with bug eyes, people just can’t get comfortable with it. Then you have the Black perception of me, and this is where it gets complicated.

From my own personal experiences, I have found that younger Black men find biracial women, myself inclusive, more attractive than fully black women. There is a societal element of colorism that makes Black men often likely to pursue lighter skinned or biracial women because of their fairness and closer resemblance to White women. I have also found that, at the risk of sounding like a completely narcissistic bitch, Black girls react in a polar manner toward biracial girls as well. Darker skinned black girls have often disliked me, and made it apparent. I’ve been verbally attacked for ‘thinking [I was] better than [them]’ because I am light, and part White. I feel like society today has beaten the dead horse of Black-White relations to a pulp, but in recent years, people are becoming wholly more aware of the larger elephant in the room – intra-Black relations and stigma.

In the novel “On Beauty” written by author Zadie Smith, she explores the dynamic of a biracial family. My favorite quote from that book (while it is a long one) comes during the fight following the realization that Howie, the unlikeable protagonist, has been cheating on his wife, Kiki Belsey. It lends itself to the black woman’s perception of her role in society because of race, and her white husband’s preferences.

A little white woman, . . . [a] tiny little white woman I could fit in my pocket.’ . . . ‘And I don’t know why I’m surprised. You don’t even notice it – you never notice. You think it’s normal. Everywhere we go, I’m alone in this… this sea of white. I barely know any black folk any more, Howie. My whole life is white. I don’t see any black folk unless they be cleaning under my feet in the fucking café in your fucking college. Or pushing a fucking hospital bed through a corridor . . .

In truth, Howie loved his wife’s regal Black features and her curves, and his preferences in his infidelity were not conscious of race or superiority. The novel goes to great lengths to show that, in fact, Howie was just an asshole. Much of the stigma Kiki felt she faced was in her head because she spent so much time being the only Black woman around her husband’s circle of academics.

In my research for this post, I found a documentary titled “Dark Girls” directed by B. Channsin Berry and Bill Duke. It explored colorism primarily among Black women, but also among Koreans and Latin Americans. One woman recalls back to middle school when she and her friends would fight lighter skinned girls in the bathroom “just because”. She is able to look back regretfully and realize that she acted out of jealousy and resentment. The scrutiny she faced from society filled her with anger that she wrongfully channeled at the these girls. She explained that the fairer girls received all the attention from the boys as being pretty and smart, with beautiful skin and hair, and it made them jealous; shamefully, she admits that some friends of hers even threw balls of nair at them to make their hair fall out. The tension between light skinned and dark skinned girls is a very real and tangible one.

In my research for this post, I found a documentary titled “Dark Girls” directed by B. Channsin Berry and Bill Duke. It explored colorism primarily among Black women, but also among Koreans and Latin Americans. One woman recalls back to middle school when she and her friends would fight lighter skinned girls in the bathroom “just because”. She is able to look back regretfully and realize that she acted out of jealousy and resentment. The scrutiny she faced from society filled her with anger that she wrongfully channeled at the these girls. She explained that the fairer girls received all the attention from the boys as being pretty and smart, with beautiful skin and hair, and it made them jealous; shamefully, she admits that some friends of hers even threw balls of nair at them to make their hair fall out. The tension between light skinned and dark skinned girls is a very real and tangible one.

Even as a young adult, I am faced with the same level of colorist tension that I received as a kid. As recently as this past weekend, I found that when I spend time with my Black friends, certain mannerisms of mine change and become ‘blacker’. If I fail to make these changes, I am clearly marked as an outsider. Because of this, I tend to keep a very diverse group of friends with whom I feel I can be myself. For example, I am Black and White biracial, with a South Indian boyfriend, and presently due to a health condition I will be unable to give birth, so we plan on adopting kids from Ethiopia, Morocco, and India. I am fluent in French and currently studying Russian. I am not a stereotype, and I implore anyone reading this to find one in which I fit. My friends look and act nothing like me; we come from different backgrounds and have different stories. So this lends itself to the question, where do biracial kids fit?

I challenge you, have you ever seen two biracial kids as friends? Possibly, but here – I challenge you even further, have you ever seen two biracial people in a relationship? Nope, never. You absolutely never have and likely never will. And do you know why? Because for some reason, mixed kids rarely find each other. Biracial people, we can spot another biracial person a mile away, and we can usually identify their mix and the ratio of each race. I have one friend that jokes that if she hears a voice ask, “Are you mixed?” she knows it’s me. And it’s true! Never before in my life have I known biracial kids, so here, in a school of 20,000, I realize that we are a real tangible population.

One of the most confusing aspects of the biracial population is that we are so dispersed in society. As I stated before, we are rarely ever together; it’s an anomaly if we are. Because of this, it allows for the question of whether we actually are a community. Personally, I believe so. We have mannerisms and language specific to us, that other people don’t quite understand. It’s commonalities like these that bring us together on the few occasions we actually cross paths. I cannot tell you how many times in a day, people ask me either “Can I touch your hair?” or “So what does your hair look like when it’s not straight?” Let me tell you, if I had a dollar for every time… But that’s the truth of it! People genuinely don’t know.

American society unintentionally lumps biracial kids into the same pile as twins, people from the UK, Italians, and sassy toddlers. We’re bombarded with a series of questions and requests to satisfy their curiosity about the alien nature of our being. And a lot of the time, not to sound like a sob story, it’s really hard! It’s frustrating when your mom doesn’t understand why you need to buy conditioner for your hair so often, and when your boyfriend asks why he never sees you shampoo your hair, or why you like tanning even though you’re half black, or why you jumped for joy when you realized College Board let you check multiple ethnicities. It’s the biracial specific isms that bring us together.

When I met my first biracial student at Syracuse, it was at a small hang-out at my friend’s apartment. He was very fair with freckles, and when I saw him I asked, “Are you mixed,” to which he replied yes.

His friend then asked if I was. He answered for me and said, “Yeah, she’s Black and White, too.”

That same friend asked how he knew, and we both replied simultaneously, “It’s a mixed kid thing.”

And it is. A conversation then budded about which parent was Black and how being mixed affected our childhoods and the kind of friendships we held and the experiences we each had. The real bonding moment was when we talked a bout how annoying it is when people always ask why we’re so light – why we don’t look like what a mixed kid should look like.

bout how annoying it is when people always ask why we’re so light – why we don’t look like what a mixed kid should look like.

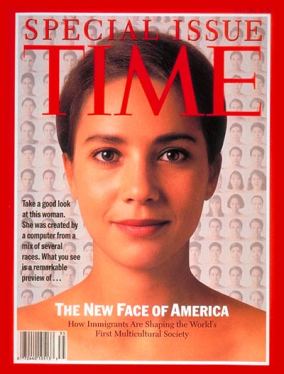

“TIME” magazine published an issue focused on “the new face of America” and mixed race people. I found the cover of the issue is particularly interesting because it is of a computer generated woman’s face, composed of different races. While you can clearly distinguish what ethnicities and races were likely used, you are unable to put your finger on exactly which feature comes from which race. This creates a feeling of uneasiness, but the heterosis allows the viewer to feel comfortable with the ambiguity of her features. Biracial kids will only become more mixed race as time progresses and it will be in that time that we reach a level of ambiguity in populations that allows us to comfortably exist.

Smith, Zadie. On Beauty: A Novel. New York: Penguin, 2005. Print.

http://officialdarkgirlsmovie.com/about/

http://content.time.com/time/covers/0,16641,19931118,00.html